What is your race?

A seemingly harmless question, especially when it comes to the U.S. census and other forms of data collection.

But what happens when your identity doesn’t exactly fit into the categories given to you?

The day I took my PSAT was the first time I realized I was white.

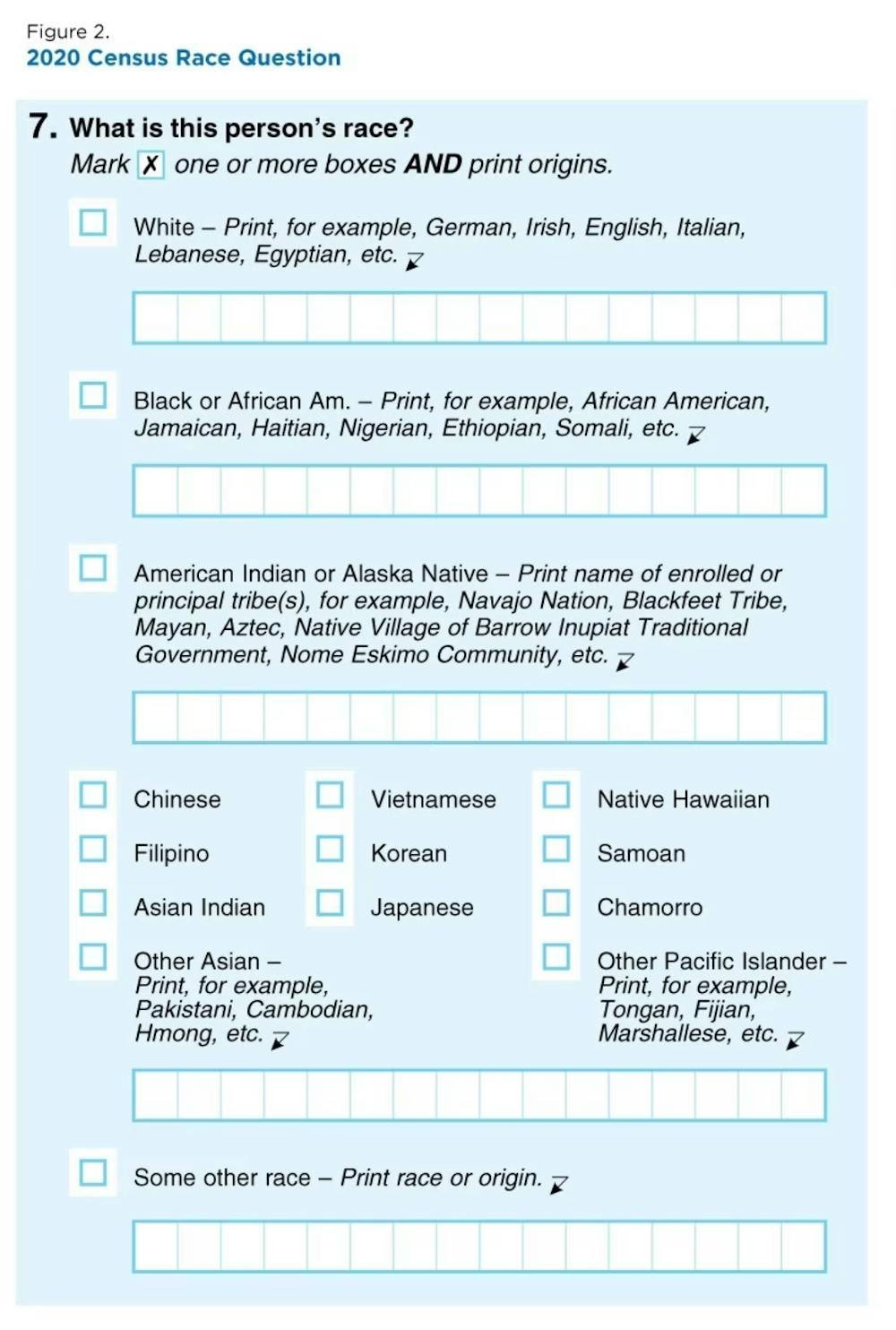

I had been filling out my name, age, and sex – all standard protocol. But then I got to the race/ethnicity section. My options included: Hispanic/Latino or Spanish origin, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White (including Middle Eastern origin).

I stopped.

White (including Middle Eastern origin).

I hadn’t even begun taking the actual PSAT, and I was already confused. As a Palestinian American, how was I considered white?

From my own personal experiences, I was not given the luxury of being called white whenever people knew I was Palestinian. However, what other option did I have? I circled white and began taking the exam, but this incident didn’t leave my mind.

Many Americans who identify as Middle Eastern and/or North African (MENA) have struggled to answer the question of race/ethnicity identification for decades.

Out in public, they're considered people of color or part of a minority. On the other hand, according to the U.S. Census, anyone of MENA descent is considered white. The issue with such classification is that this group of people is faced with a double-edged sword: they’re regarded as white on paper but treated as “others” in the real world.

The U.S. Census claims to collect racial data to help “federal agencies monitor compliance with anti-discrimination provisions, such as those in the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act.”

Are they really able to accomplish that without accurately counting an entire group of people whose numbers are growing by the day? The answer is no. MENA Americans have dealt with misrepresentation in multiple capacities due to a lack of proper identification, whether it comes to the media or even the population.

On a deeper level, these individuals can’t know where they fit in when it comes to either American or their own cultural societies.

Rather than being hidden within the White or Other categories, MENA Americans deserve to be counted within their own group and finally have their own identity.

1) Census and History

Realizing I was technically white sent me down a rabbit hole to figure out the question: What am I?

After watching a video on YouTube titled “Are Arabs ‘White’?” that discussed the history of Arabs in America, the pieces of the “identity puzzle” began clicking into place. When the first Arabs arrived in the US in the 1880s and 1890s, they were barred from becoming naturalized citizens because of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Since most of these Arabs came from Lebanon and Syria, which are technically in Asia, they were subject to this discrimination. Their right to become naturalized became the fight to be classified as white.

The most notable changes occurred in 1915, 1944 and 1977.

In Dow v. United States (1915), the United States Court of Appeals ruled that Syrians were included in the term “white persons.” This ruling only applied to Arabs from the Levantine until 1944 when the federal government deemed all Arabs (including those from North Africa) as white. By 1977, the Office of Management and Budget’s Directive No. 15 defined a white person as “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, North Africa, or the Middle East.”

While these advancements were beneficial for Arabs when they first arrived in the US, times have changed. It’s an issue that the U.S. Census does not have a category for people of MENA descent as now we have become an invisible minority, hidden in between the labels of “white” or “other.” There is no accurate count of how many MENA citizens live in the US. This has led to decades of inadequate Arab representation in the media, and in health demographics, and brought about uncertainty when it comes to identifying a diverse group of people. As a result, President Biden’s administration is once again revisiting this topic as groups speak out in support of a MENA category.

2) The Arab Experience

Being Arab in America can’t exactly be described just by one person’s perspective; every MENA person has their own personal experience with their identity and ties to the Arab classification. It’s also important to note that with the MENA term, people who identify as North African might not always consider themselves Arab. This is due to the historical contexts within that area, specifically within the countries of Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Morocco.

While my experience focuses on the Arab/Middle Eastern side, it is one that encapsulates a lot of the identity struggles for MENA youth. I was born in the US, raised by Palestinian immigrants and grew up in a predominantly white town. Arabic was the only language we spoke at home for years until I began attending public school and started bringing more English into the house. I was stuck between two worlds: I wanted to be seen as a typical American outside of the house, but I also wanted to fit into my family’s culture.

The main aspect of my experience is to highlight the identity crises that many MENA American youth deal with: the idea of never knowing where you truly fit in.

If I could describe growing up in America as Arab in one word, I would pick the word “wishing.” I grew up wishing to see a girl like me on television, wishing to not feel like an outsider among my peers at school and wishing my culture was celebrated among others in the classroom.

Growing up in a post-9/11 world, most Americans saw the Arab world in a negative light without even realizing it. When I was six years old, I remember kids on the bus asking me where I was from and their confusion when I mentioned my family was from Palestine.

“Do you mean Pakistan?” they asked.

I shook my head. “No, that’s another country. I’m from Palestine.”

“Are you sure? Maybe you’re Indian,” they said.

“I speak Arabic, that means I’m from Palestine,” I insisted.

These conversations would go around in circles, leaving me frustrated as a child.

Eventually, I gave up on telling people I was from Palestine, deferring to telling them my grandma lived in Egypt. Unfortunately, that led to more questions about how she survived living in a desert.

Such conversations left me feeling like an alien among my peers despite the fact that I was born in America like them. Because of my background, there was a level of disconnect; they didn’t see me the way I wanted to be seen. I went from wishing for others to understand my culture to wishing I was white. I constantly asked myself, “Why couldn’t my family be from just New Jersey?”

I decided that I would try to erase all aspects of what made me different – I’d focus on being only American. From elementary to middle school, I stopped speaking Arabic at home in an attempt to improve my English. When people asked where I was from, I’d just say the town I grew up in. I begged my mom to make me peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on regular white bread instead of pita. Foolishly, I thought this made me the same as everyone else despite my name clearly reflecting my Arab heritage. Nevertheless, I assured myself that I was now just American, and I was the happiest I could ever be.

Until I reached middle school.

Soon, I couldn’t speak Arabic as well. I forgot words constantly, mispronounced them, replaced them with English words, and I couldn’t read or write. When I had to talk to family members on the phone, they began ridiculing my broken Arabic and asked me if I even understood them. I felt a sense of shame; I destroyed a part of my identity.

It took me years to regain what I lost – I had to reconnect with my culture by taking Arabic classes, learning to speak more frequently with family members without using English and exploring new relationships with other Arabs my age.

Embracing my cultural identity didn’t resolve everything as I became more aware of the prejudices people had towards Arabs. There’s a fine line when it comes to curiosity about one’s culture versus being misconstrued by ignorance. Whenever we talked about September 11 in class, all eyes turned towards me as if I was directly involved in the tragedy. Classmates have asked me if I was going to have an arranged marriage, if my parents were going to let me stay in school or if I even liked Americans (even though I was one). It was almost as though if I was too prideful in my Arab identity, people questioned how American I could be.

3) Representation

Why did people struggle to understand that Arabs could be American as well? These misconceptions stem from the inaccurate representation of Arabs in Western media, which has portrayed an entire group of people in a negative light since 1896, according to Jack Shaheen’s Reel Bad Arabs.

Popular films such as “Back to the Future” (1985) and “Aladdin” (1992) featured negative portrayals of Arabs and contributed to the confusion behind the MENA identity.

In “Back to the Future,” Doc and Marty were in the parking lot with the time machine when, all of a sudden, Libyan terrorists began attacking and yelling in Arabic. During the 1980s, the U.S. and Libya weren’t exactly friendly, especially after the U.S. closed Libya’s embassy in Washington in 1981. However, the filmmakers didn’t have to make the villains Arab; they could have just had opposing scientists who wanted the plutonium from Doc in the scene.

When I watched “Aladdin” as a kid, I remember thinking that it was a great Disney film because it had Arabs. As I got older, I recognized how flawed the film was, adding to negative stereotypes of my culture. Disney mixed South Asian and Arab cultures, so that they’re indistinguishable, which makes it even more confusing for Americans to understand Arab culture.

The film still managed to portray Arabs as the bad guys with the villains having accents and looking more “ethnic” (Jafar), while the protagonists spoke perfect English and had more European features (Aladdin and Jasmine). Even the original lyrics to “Arabian Nights” alluded that Arabs were violent: “Oh I come from a land, from a faraway place/Where the caravan camels roam/Where they cut off your ear/If they don't like your face/It's barbaric, but hey, it's home.”

After watching films like these two, and hundreds of others that include similar stereotypes, it’s not hard to realize why Americans might view Arabs in an unfavorable light. It also offers a reason as to why Arabs might not want to have a MENA category on the census as it would mean giving up the white title and being classified as villains.

Maybe if filmmakers knew the actual number of the Arab American population they might have made different choices on how to portray MENA characters in American media. In the 1980s, there were around 625,000 Americans who identified as part of MENA, according to the U.S. Census ancestry question; that number grew to 850,000 by 1990 and up to 1.2 million by 2000. This data isn’t completely accurate because the ancestry question only accounted for specific ethnicities from the MENA region (Lebanon, Syria, Iran, and “Arab/Arabian”).

Without a dedicated MENA classification, other organizations have utilized surveys in an attempt to find more accurate data on the Arab American population. In 2018, the Arab American Institute Foundation released their estimate of the Arab American population to be around 3,665,789 compared to the U.S. Census’s 2,041,484; inaccurate federal counts lead to an inaccurate American perception of an entire group of people.

4) Conclusion

Ultimately, including a MENA option on the U.S. Census won’t resolve every issue when it comes to Arab identity and representation. However, it is a start necessary to get change in motion. MENA Americans already fought for the right to naturalization in the 1890s, so now is the time to fight to be recognized as a substantial part of the American population.

Dareen Abukwaik can be reached at dareen.abukwaik@student.shu.edu.